How to publish your research: the journey from composition to publication

As early-career researchers begin to develop their research in the hope that one day it will be published, how do they take those first steps into becoming published authors? Who do you talk to? Where do you start?

In this piece, we outline what stages are involved in publishing research to help support those wanting to publish their final research and become authors, providing clarity behind this process. Also, industry professionals and previous Bioanalysis Rising Star Award (BRSA) winners provide some tips and advice about their experience with the writing and submission process to help guide others.

The publishing process

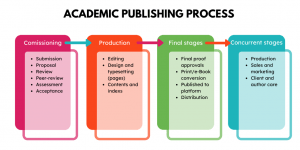

Most publishers have slightly different steps within their publishing process, but this is the basic outline of what happens at the key stages of publishing research within a journal:

Submission

First, an initial submission to the publisher is made by the scientist or researcher, which is then reviewed by the editorial team within the publishing house, who assess all submissions. The editorial team debate whether an article will fit within an upcoming or future journal issue. This is then often sent for further peer-review to an external group of industry experts who ensure the material’s accuracy and reliability and provide their own comments on the piece.

Peer-review is the process of evaluating articles before publication to maintain the integrity of the science by filtering those that do not meet industry standards. The group of reviewers are usually volunteers who are experts within the article’s subject matter and their method of review varies from: single anonymized review, double anonymized review, triple anonymized review and open review.

- Single anonymized review: this is the most common method of reviewing; it is where the names of the reviewers are hidden from the author. This allows an impartial review as reviewers are not influenced by any author contact when conducting their review.

- Double anonymized review: this is where both the reviewer and the author are anonymous to each other. This limit’s author bias and focuses on the content of the article piece.

- Triple anonymized review: with this type of review, reviewers are anonymous, and the author’s identity is hidden from both reviewers and the editor. This limits bias from the submission stage but is complex considering the level of anonymity.

- Open review: this is where both the reviewer and author know each other’s identity during the peer-review process. This method can offer open and honest reviewing but may tone down criticism.

Overall, editors have the deciding factor on whether a piece is accepted, needs revising, or is rejected. If a piece is rejected, feedback should be reviewed, as a rejection does not necessarily mean that the article is not worth publishing at all.

Bioanalysis and peer-review

“Future Science titles aim to ensure that articles are unbiased, scientifically accurate and clinically relevant through a rigorous peer-review process. Articles are peer-reviewed by two or more members of the International Editorial Board or other specialists selected based on experience and expertise. Review is performed on a double-blind basis.” – Laura Dormer, Editorial Director, Future Science Group (London, UK)

For more information, click the link>>

Production

Once an article is accepted, it then goes through the production process, which varies between physical and digital publication. This involves editorial, design and production departments, all of whom work to produce the journal, making sure it is of a high-quality standard and that the articles fit the publisher’s layout. This is then sent for the author’s approval and corrections, if any, are made. Once everything is approved, the article is published online so that others may access the research.

Research can be published via open access, a publishing model for scholarly communication that makes research content available to readers at no cost, as opposed to the traditional subscription model. There are a few types of journals, some that include Open Access, such as: subscription, hybrid, and gold open access journals.

- Subscription journals: all content is behind a paywall and is accessed via individual subscriptions.

- Hybrid journals: a mixture of open access content and content that sits behind a subscription paywall.

- Gold open access journals: allows publications to become immediately available as soon as they are published.

- Delayed open access journals: articles are openly available, like gold open access, at the point of expiry of a set embargo period.

Open access is important for research because of the worldwide visibility without barriers, which demonstrably leads to more citations, more impact and more visibility, thus increasing new research and study ideas. For both digital and physical publications, relevant articles are collated to create the journal title alongside other relevant content. This is then either made accessible online or files are sent to print and physical journals are produced.

Bioanalysis and open access: at Bioanalysis we are a hybrid journal that also provides a range of fully ‘gold’ open access articles. We also provide ‘green’ open access, also known as self-archiving, which is the process of archiving a copy of the research article elsewhere.

More information can be found here: www.tandfonline.com/authorguide/openaccess

Advice from experts: how to write and submit research

Jing Tu

DMPK Group Manager, AbbVie (MA, USA)

Firstly, do not be afraid of abnormal data. Abnormal data does not necessarily mean something is wrong, it could also mean something is new. After ruling out the operational and calculation errors, abnormal data will probably indicate unique feature(s) regarding the molecule of interest, critical reagents and/or the biomatrix. In the field of bioanalysis, research is extremely practical and unique innovations should always tie back to a unique finding from the bench.

Secondly, read, read, read. Keep up-to-date with bioanalytical publications, so that you have a good sense of whether similar solutions have not been published in the past. Also, reading will help you identify the current industry pain points and the hot spots of the bioanalytical front. Specialized journals, such as Bioanalysis, are a great resource for such information.

Thirdly, leverage all the resources available. Always seek advice and input from senior staff(s), mentor(s) and peers. Some early-career scientists can be very shy. They may experience unnecessary self-consciousness if they believe their questions are too ‘simple’ or ‘naïve’. From my experience, most senior scientists are more than happy to help junior scientists with their queries.

Lastly, always keep the curiosity and passion towards scientific research!

Matthew Ryen Lockett

Associate Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (NC, USA)

Before writing anything, I generate a modular block diagram and rearrange each block until I map out an appropriate story arc for the paper thus providing context and insight for both the novice and expert reader. This approach was born from the necessity to choose the most impactful papers to engage with, given my limited attention span and time.

How do I engage with the literature? On the first pass of any paper, I focus on its figures and look for two components. First, I look for a comprehensive overview figure. Nothing is more valuable to me than a figure that provides and explains the approach of the study. Second, I focus on the data. Data figures that, along with their caption, provide enough information to understand the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of the experiment(s) are imperative for me to evaluate the thoroughness of the study. On my second pass, I carefully read the introduction, results and materials and methods sections. A good introduction skips banality and provides insights that come from deep and prolonged thought of the subject. A successful results section provides context for the ‘why’ of each experiment and the logical flow for subsequent datasets. The materials and methods section has the detail needed to assess conditions and controls.

My writing approach—the transition from the block diagram to a bulleted outline to paragraphs—emphasizes my approach to reading the literature. When have I reached the final product? With the figures and paragraphs in place, I read the sections aloud and evaluate on the following criteria. Does the introduction provide the background knowledge necessary for the reader to appreciate the results? Are the results presented concisely (are the setup, analysis, and conclusions clear)? Finally, do the conclusions provide insight not covered elsewhere in the paper? My goal in the conclusion section is to convey my perspective, enabling others to see my vision (and hopefully build upon it).

Handy tips

- Be visible: early-career researchers need to produce high quality work and ensure that this work is noticed. Make sure you develop skills in self-promotion, as this can be essential to furthering your career.

- Raise your voice: use multiple platforms, such as social media, to talk about your research, the diversity of your career paths and publication strategies. Reach out to those in the industry and network as much as possible. Some people are willing to have a chat and discuss your questions. Try LinkedIn or Twitter, as most companies and professionals are active on these sites.

- Support, support, support: look out for workshops, conferences, industry discussions, online tools and journal mentoring programs, as getting as much support from those in the industry is vital.

- Explain why your work is important: have a clear argument throughout the sections of your paper explaining why your paper is significant to your area of study.